Digital campaigners stay connected to the pulse of online conversations surrounding their campaigns. But what happens when a crisis occurs, bringing a surge of attention to your issue?

This was the situation Greenpeace encountered as it plunged into a campaign to free the “Arctic 30” activists detained in a Russian jail following a peaceful protest on the Prirazlomnaya oil rig in September 2013.

Greenpeace is no stranger to social media monitoring, but the high volume of social media conversations and rapidly-changing story stretched the limits of existing monitoring and analysis practices — preventing the organization from fully understanding the impact its activities (and that of its supporters) were having on the global conversation.

The Mobilisation Lab (and its partners at Upwell) joined forces with Greenpeace International’s digital mobilisation specialist Juliette Hauville and Julian Gretsch, a social media analysis intern during the Arctic 30 and current mobilisation coordinator and social media specialist, to design and implement a new social listening and online media analysis program for the Arctic 30 response.

The new reports gave Greenpeace a way to know if people were connecting the arrest story to the larger campaign to stop Arctic oil drilling and provided new information and insight to the core campaign team.

Ben Stewart, head of global communications for the campaign to free the Arctic 30, found the reports useful.

“I liked the qualitative analysis that was included. What we needed during A30 was simply a sense of how our message (and the Russians’ message) was playing in different markets, and how much attention we were getting,” Ben says.

The core campaign team managing the overall response was interested in an overall sense of what people were talking about, including supporters, journalists, and opponents. The online analysis reports complemented the traditional media analysis work of another team.

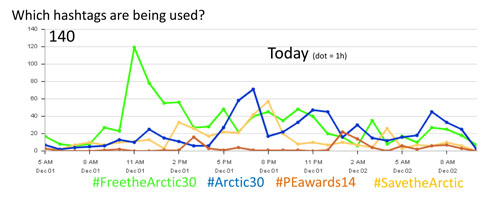

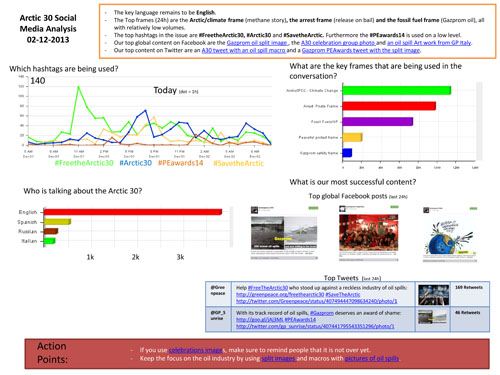

The social media team monitored what hashtags people were using in online Arctic 30 conversations.

Here are Juliette and Julian’s key learnings from the experience:

1. Know Your (Internal) Audience

Find out what kind of information people need, how much time they will spend reading it, what kind of knowledge they have and how much detail they want.

“It’s important to tailor the document as much as possible to the people who are going to read it,” Juliette says. “It was difficult for us during the Arctic 30 because all the decision makers and leaders of the project were extremely busy, so we got very little feedback on what they wanted.”

As it was a rapid-response project, Juliette says the team used a lot of intuition.

“For others who are deliberately setting up a process like this, it’s worth taking time before the project is live to have a discussion with the decision makers, before they are too busy to answer you,” she says.

When Juliette and Julian started delivering the reports, they used a lengthy format with about 20 slides of information that was not well-summarized or condensed. This report was sent out twice a day, including weekends.

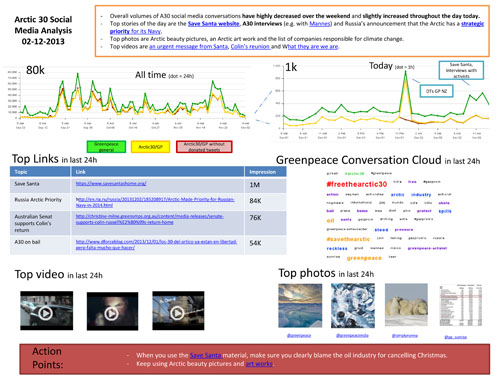

A snapshot of the top Facebook posts.

“We had no idea it would be such an intense campaign for so long,” Juliette says. “I think a lot of us were under the impression, mistaken obviously, that it would be a crisis that would last a few weeks.”

Juliette says the team soon realized that it would be inhumane to keep going at the same rate as the Arctic 30 continued to be detained. The team no longer sent out weekend reports, and decreased from two to one per day. The MobLab worked with them to create a more effective two-page format (see more under tip 4).

2. Combine Multiple Tools to Capture Key Data

When it comes to social media analysis, there isn’t one tool that will give a perfect tracking picture. Using a few can overcome limitations.

To track external networks, the team used the following monitoring tools:

-

- Radian6 – used to track different frames — angles to the story looking at what kinds of words people use when they talk about the issue — as well as overall volumes of mentions. Julian notes he put time into building up keywords, which is useful for real-time monitoring.

- Topsy Pro – monitored particular hashtags, provided an overview of the most effective images, videos, links and tweets in specific keywords sets for issues.

To track Greenpeace-related accounts:

-

- Crowdbooster to check what is working on Twitter and Facebook accounts.

Other tools:

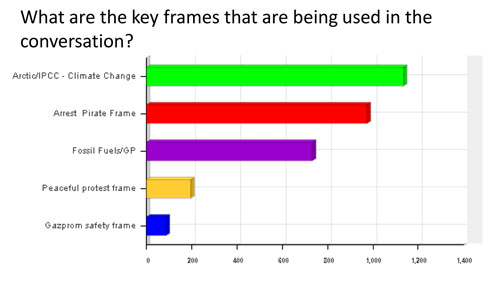

Looking at what kinds of words people use when they talk about the issue was another element the team analyzed.

3. Work with Others to Surface Key Insights and Action Points

Getting together in person with others working on the campaign to discover key observations, learnings and action points from the tools — rather than relying on the tools to analyze — is key.

Juliette says she’d recommend the approach they took: four or five people working on social media output and analysis sat down together to discuss the findings and come up with action points.

The data provided an ongoing reality check, Juliette says, as the online media analysis report statistics showed what messaging was resonating and who was dominating conversations. Because they knew what online messaging was resonating best, the team could focus on that and optimize their online mobilisation efforts.

Through the use of frames — a tool that looks at what words people use when they talk about the issue — and developing different keyword sets the team could provide an overview of what angles in the issue were being used in discussions over time.

“I think that was valuable in order to see what kind of angles work and what kind of things don’t resonate so much,” Julian says.

4. Design a Friendly Format

A helpful report is easy-to-read and visual, no more than two pages, with a clear summary and clear action points. (See sample report below)

Julian recommends using the same format each day and including visuals such as graphs. Condense the main points into two slides. The team used PowerPoint to produce the report and then delivered them as PDFs via email and Greenpeace’s intranet.

“Quite often we try to make it visual and clickable,” Julian says. “People were able to get a good overview. In reality, lots of people only had a couple of minutes, or sometimes even seconds, to look at it and should be able to directly see what is going on.”

It’s difficult to determine what to summarize and what to leave out, Julian notes. “When you look at the graphs you know much more and you have the urge to tell everyone the whole story, but it’s the art of summarizing.”

5. Create a Process for Follow-up.

While the team didn’t have this in place during the Arctic 30 campaign, a follow-up process is something they learned is important.

Given the nature of the Arctic 30 situation, it was difficult for Juliette and Julian to receive feedback on their reports and measure their impact. But when they mentioned stopping or slowing down the reports, the recipients wanted them to continue, signalling they were of value.

“It’s so easy to have these reports coming into someone’s inbox every day and happily ignore them, and then it’s a waste of time,” Juliette says.

“But if you have a system in place, ‘OK, we get this and this is what we’ll do with the knowledge we have from this report’ — it ensures no one’s time is wasted and we really learn from the data.

“That was my biggest lesson learned. Don’t assume that just because you are providing information they are using it. Have a process for it.”

Ben also notes the importance of dedicating attention to this type of new activity through, for example, assigning someone the responsibility to bring the intel from the online media reports into the campaign meetings to ensure people are aware of the information.

Example Report

Stay Connected

Related Posts

- Digital storytelling lessons from the campaign to free the Arctic 30

- Spark innovation with data

- ‘Global Think Tank’ empowers staff in massive organizational moment

Do you have an innovation in mobilisation and people-powered campaigns? Share it with MobLab by contacting moblab@greenpeace.org.

Categories:

testing, learning and iteration