As a social media analysis intern at Greenpeace International, Julian Gretsch says he is not someone who can usually submit ideas on the strategic level. But he was able to do just that when the organization was in the global spotlight and looking to help free colleagues from a Russian jail.

Julian submitted his idea to help the Arctic 30 Greenpeace activists who were detained following their peaceful protest at the giant Prirazlomnaya oil rig in September 2013. Through the launch of a “Global Think Tank” and an invitation for all staff to share their creative ideas, Julian suggested connecting football fans to the issue, as oil giant Gazprom heavily sponsors sporting events. The idea was implemented, though Julian says he’s not sure if it was linked to his concept or if someone else had the same idea in motion already.

“(The Think Tank) was a great start and tool,” he says, noting with this kind of crowdsourcing platform there is a higher chance of getting strong ideas and it empowers people because they get more involved.

Breaking Down Bottlenecks

With the 28 activists, a freelance photographer and a freelance videographer held in a Russian jail, the rest of Greenpeace was looking to do everything possible to free their colleagues.

“It became the kind of thing where everyone was expected – and ready – to drop everything else they were working on,” says Michael Silberman, global director of Greenpeace’s Digital Mobilisation Lab.

“But despite major contributions from many staff around the world, it seemed like a majority of Greenpeace staff didn’t know what they could do to help beyond amplifying the story online or attending local events.”

One important factor was that staff were scared to take a misstep during such a high stakes moment. Furthermore, with most communication coming top-down from an officially designated core team, it was difficult for most staff to see how they could contribute beyond supporting specific initiatives communicated by the core team.

“Any existing senses of hierarchy and sign-off were amplified, if only through perception,” Michael explains.

Five Greenpeace International activists attempt to climb the Prirazlomnaya, an oil platform operated by Russian state-owned energy giant Gazprom. © Denis Sinyakov/Greenpeace

The impetus to create the Think Tank came from two coinciding events – a discussion that the MobLab had with the campaign coordination team, which expressed frustration that more staff and offices weren’t driving new initiatives to support the effort, and an executive directors meeting where leaders expressed interest in having their offices do more to help the Arctic 30.

The MobLab and Greenpeace Argentina executive director Martín Prieto explored several solutions – including issuing a creative brief to all staff. Ultimately they settled on creating an online forum and program (or “Global Think Tank”) that invited anyone across the organization to share and cocreate ideas to help free the Arctic 30.

Creating an Open Creative Space

The Think Tank launched on Greenpeace’s intranet, Greennet, on Oct. 28. Greenpeace International executive director Kumi Naidoo sent an e-mail to all staff inviting them to bring ideas and creativity forth through the platform.

With approximately 3,000 Greenpeace staff members around the world, the Think Tank provided a way to harness the collective intelligence of the organization and enable anyone to to voice ideas.

“This was a way of saying that you don’t have to be a campaigner to contribute to this effort. Whether you’re a receptionist, a finance director, or a mechanic, you’re invited because we know that you have good ideas too,” says Martín.

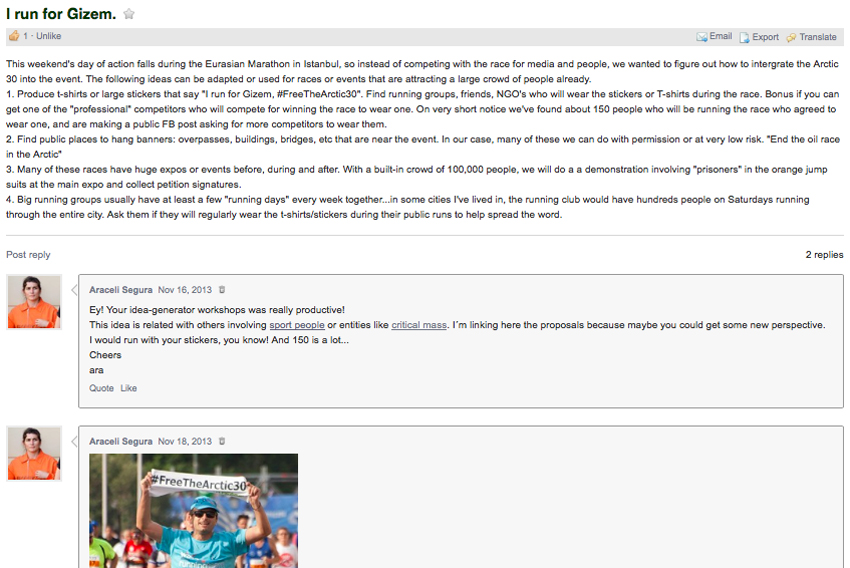

Araceli Segura, Latin America developer with Greenpeace’s Vol Lab, facilitated conversations and reviewed all of the ideas posted. She encouraged and helped people with their ideas, grouped ideas and ensured the central campaign coordination team was aware of ideas being developed.

“In a sense, we were building the internal community of Greenpeace because (staff) started conversations in a way they can’t do in other places,” she says.

Following a wave of initial ideas and intense traffic, facilitators created a new “Ideas in Progress” page to highlight projects that were becoming a reality. By mid-November, more than 60 ideas were on the site.

As part of the Think Tank, MobLab’s Tracy Frauzel created an Arctic Ideation Toolkit to assist offices and groups with brainstorming. The toolkit explains how to run an ideation workshop and convene a group of people in collaborative exercises to generate and build on ideas. The workshops generally last one and a half to two hours.

The Ideation Toolkit sought to augment the online or e-mail brainstorms, notes Michael. “We believe the real creative ideas come when people put their heads together, step back in and create a space to do that,” he says.

There were multiple levels of support for the Think Tank, including the executive directors, campaign team and senior leadership working with practitioner communities. Working with these different levels of the organization was key to making the Think Tank happen, says Michael.

Building and Acting on Ideas

The Think Tank has been used in different ways for different people, says Araceli. Some used it to share personal ideas, to develop activities, to get inspiration, to talk about the campaign and to express strategic thoughts.

“This site was (a place to) give your idea and if you can do it, do it, and if not, maybe another person can do it instead of you. And that happened,” says Araceli.

Some of the implemented ideas include a global flashmob day, having volunteers “jailed” in a main streets, and adding comments to Shell and Gazprom gas stations on Google Plus’ Maps.

The Google Maps idea came from a Greenpeace Argentina campaigner. It is simple concept and can be organized with Greenpeace staff and volunteers at the same time, says Araceli.

From its launch at the end of October to its natural close in December, prior to the Arctic 30 being granted amnesty and released, staff contributed a total of 92 ideas to the Think Tank, 24 of which moved on to implementation. The 126 participants contributed more than 270 comments to help improve the ideas posted to the feed.

Araceli notes it is difficult to measure the Think Tank’s impact in the final development of campaign activities, as many ideas were adapted and evolved during implementation.

This Think Tank screenshot shows a participant’s idea to integrate the Arctic 30 Day of Action into the Eurasian Marathon in Istanbul. Araceli provides feedback in the following thread.

Takeaways

Overall, the ideas, feedback, and conversations generated by Think Tank participants were high quality, observes Araceli, and surfaced ideas that otherwise may have never made it into the Arctic 30 response effort.

“This enabled us to shake loose some of the great thinking that already exists but wouldn’t necessarily break through our hierarchy or the distributed nature of a big organization like ours,” Michael notes. “It was an important test case in becoming a better networked, more nimble, responsive, creative organization. This project connected people across offices and borders in a way that doesn’t often happen.”

It’s rare any campaign receives the kind of international attention garnered through the Arctic 30, he notes.

The Think Tank approach was also good for Greenpeace’s internal culture. “When people really can leverage all of their skills and talents, they not only feel better about themselves but are also able to contribute more to the organization,” says Araceli. The Think Tank also helped to build community in a way that’s consistent with how Greenpeace looks to engage with its supporters and volunteers, Araceli noted.

The Think Tank organizers share a few lessons learned for future campaigns and efforts interested in applying this approach:

- Group ideation workshops are valuable but require a big investment in organizing and outreach. Araceli notes that ideas may be more powerful and realistic to implement when several people create and refine them together, compared to people submitting ideas on their own.

- Identify volunteer facilitators in each office who can be responsible for the creative process and support staff who are interested in participating but need encouragement or aren’t sure how. Think Tank organizers had limited success identifying facilitators in each office on such short notice.

- To maintain momentum, explore ways to make the Think Tank new and interesting each week. Send updatesthat show progress and give people reasons to come back and see what’s new.

- Give it time. The organizers kept the Think Tank open for weeks, which meant that people didn’t have to try and be creative and brilliant in one day, Araceli noted.

- Create a list (or tag) for ideas needing support. Early on, some of the ideas submitted required other people to implement. Create a way for participants to flag ideas that need to be adopted.

- Be flexible. Some Greenpeace participants were very creative and proactive in how they used the platform. For example, someone created a page for new situations that may emerge if the activists were freed. Be ready to support and encourage positive contributions that may be different from the initial plan.

Stay Connected: @silbatron @SeguraAra @savethearctic

Related Posts:

Dissection of two days of action to #FreeTheArctic30

Do you have an innovation in mobilisation and people-powered campaigns? Share it with MobLab by contacting moblab@greenpeace.org.