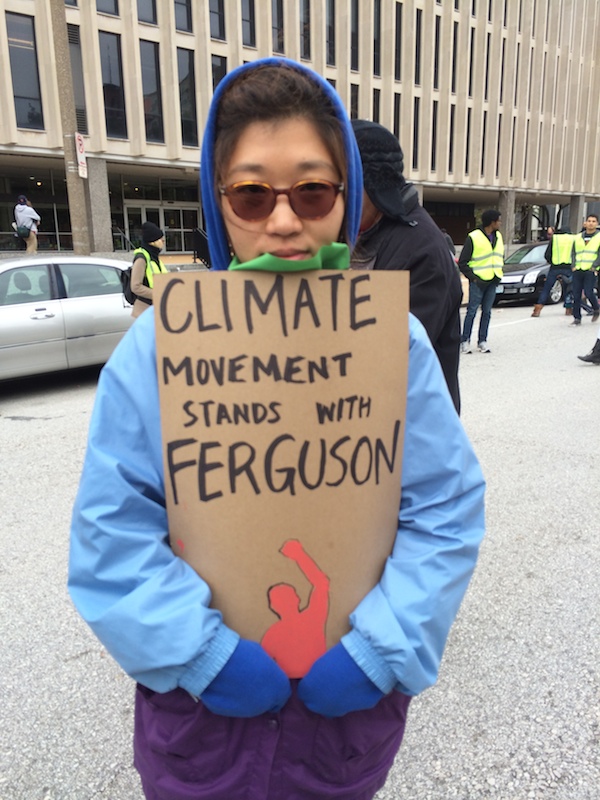

Thousands of people converged on St. Louis for Ferguson October, four days of marches, rallies, sit-ins and prayer meetings protesting the fatal shooting of unarmed black teen Michael Brown by a Ferguson police officer. The events drew support from multiple movements, with representatives of Occupy, labor unions, gay rights groups and Palestine in attendance. A climate contingent led by 350.org and Energy Action Coalition was also part of the crowd, quietly swelling the ranks.

At least two dozen climate activists traveled to St. Louis from as far away as Minnesota, West Virginia and New York. A few individual climate activists reached out to local organizers to ask what needed to be done. Arielle Klagsbrun of Missourians Organizing for Reform and Empowerment (MORE) suggested they organize a climate contingent, similar to the Palestinian contingent that was planning to come. Yong Jung Cho, a Fossil Free organizer with 350.org, and others pulled one together in only a week’s time.

Just a few weeks after the People’s Climate March drew an estimated 400,000 people (some with “Hands Up Don’t Shoot” signs) to the streets of New York to demand global action against climate change, Ferguson October was an opportunity for People’s Climate leaders to reciprocate the cross-movement support. On the Wednesday preceding Ferguson October they posted on their Facebook page: “As part of a movement of movements, we support those organising for racial justice in Missouri this weekend!”

At least two dozen climate activists traveled to St. Louis from as far away as Minnesota, West Virginia and New York. Photo courtesy Maryam Adrangi.

Don’t Just Show Up — Get Behind and Lift

The environmental movement has in the past been perceived as an “upper-middle class, white male” cause, and the diversity visible at the Climate March—which was led by “two full city blocks of indigenous peoples”—was seen as one of its greatest victories.

“The climate movement at large is still learning how to stand in solidarity with other movements,” Cho explains.

Practically speaking, that’s ‘learning’ not only how to show up, but what to do once you’re there.

“I think we started out thinking solidarity meant, you know, showing up with a climate delegation, organizing our own signs and banners, marching as a group, etc.,” says Joe Solomon, social media coordinator at Energy Action Coalition.

“And when we got there—well, we started to realize that maybe what was really needed was not an off-to-the-side group, but rather just good old, classic help. We started out making climate signs, but as early as Thursday night, I was with a climate friend Collin, and we were helping to make banners with Organization for Black Struggle and by Saturday you could find climate activists making banners in prep for the actions that were planned for Monday.”

“The climate movement wasn’t being called on to get out in front or really stand out,” he adds, “but to get behind, and lift.”

Solomon had planned on profiling climate activists who showed up but a local organizer pointed out that would not be very helpful. “We didn’t need to shine a light on privileged outsiders, but rather we needed to use to our privilege to highlight the work of local organizers, and break that story back into the mainstream,” Solomon said. He ended up helping run MORE’s social media over the weekend, to free their hands to work on logistics and jail support efforts.

(Solomon was among over 50 people arrested at one of the Moral Monday protests on October 13.)

“When reaching out at a moment like this, we were hoping for support in terms of resources (including but not limited to money), people in the streets and help with certain skill sets such as direct action,” says Arielle Klagsbrun of MORE. “Of course it’s about more than people coming to St. Louis/Ferguson. As this continues to be a historic moment for racial justice, we need climate groups to encourage their bases to connect with local groups and campaigns to build the movement nationally and particularly to donate resources as the climate movement is historically much more well-funded than the Black-led movements.”

For many in the climate movement, especially, perhaps, those who come from grassroots and community-based organizations, the instinct to partner with racial, criminal and social justice movements is both natural and highly personal. In August, Deirdre Smith, strategic partnership coordinator at 350.org, wrote an essay explaining why climate activists should stand with Ferguson. To Smith, the images that came out of Ferguson after Mike Brown’s death, of police with military-grade weapons pointed at unarmed black people, recalled the scenes of state-sanctioned violence she and her family witnessed in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

People Power Means Caring About People

“Climate change is bringing nothing if not clarity to the persistent and overlapping crises of our time,” Smith writes. “To me, the connection between militarized state violence, racism, and climate change was common-sense and intuitive.”

Smith addresses the environmental movement’s historical divisions, and points out that if mainstream climate groups want people of color to join in their fight, then they have to show solidarity in return:

“Communities of color and poor communities are hit hardest by fossil fuel extraction, as well as neglected by the state in the wake of crisis. People of color also disproportionately live in climate-vulnerable areas. Similarly, state violence should concern us all, but the experience of young black men in particular in this country is unique. Those of us who are not young black men must step up to the challenge of understanding that we will likely never experience that level of demonization. That kind of solidarity is what it takes to build real people power — the kind of power that stands up unflinchingly to injustice, and helps us all win our battles by standing together.”

– Deirdre Smith, 350.org

Maryam Adrangi, an organizer with 350.org and Rising Tide who was in Ferguson last weekend, also emphasized the importance of people power. “As climate folk, I feel like we’re always asking ourselves why people aren’t coming to our events,” says Adrangi, “but also not going to other people’s events.”

Adrangi points out that it’s not always necessary to show up and paint the town green with banners and slogans; “we just need to go as folks that care about other people.”

Joe Solomon at Justice Now march in Clayton, Missouri. Photo courtesy FANG.

Some of the climate activists already had personal relationships with local activists in St. Louis, and that to a large extent made the climate contingent possible. Sure, a group of climate activists could have independently driven to St. Louis and shown solidarity, but would they if organizers on the ground hadn’t said “yes, you’re welcome and you can be of some help”? And even if they did, would they have been as much help once they got there without friends and acquaintances to reach out to (or, in Solomon’s case, to firmly say “Hey, what you’re planning to do is of minimal help; why don’t you do this instead”)?

Personal relationships, especially early on in cross-movement organizing, are absolutely essential.

“We all have friends in other movements,” says Adrangi, “but sometimes we forget that they are all human relationships…. we build relationships [with each other] for climate organizing but that doesn’t mean we can’t use those relationships for other things.”

Stay Updated

Top photo: A climate activist banner at Ferguson October. Photo by Pia Ward.