Colin Holtz is a progressive writer and strategist who has authored several reports and articles for Mobilisation Lab, including Beyond Vanity Metrics: Toward better measurement of member engagement and “Grassroots-led Campaigns” Transforming the Landscape of Social Change. Colin joined us for Open Campaigns Camp 2015 and had these insights to share on open campaigning.

What do you get when you bring together 70 cutting-edge organizers from all over the globe to talk about opening up advocacy campaigns to members and grassroots leadership? Open Campaigns Camp 2015, sponsored by the Mobilisation Lab and Volunteer Lab at Greenpeace International.

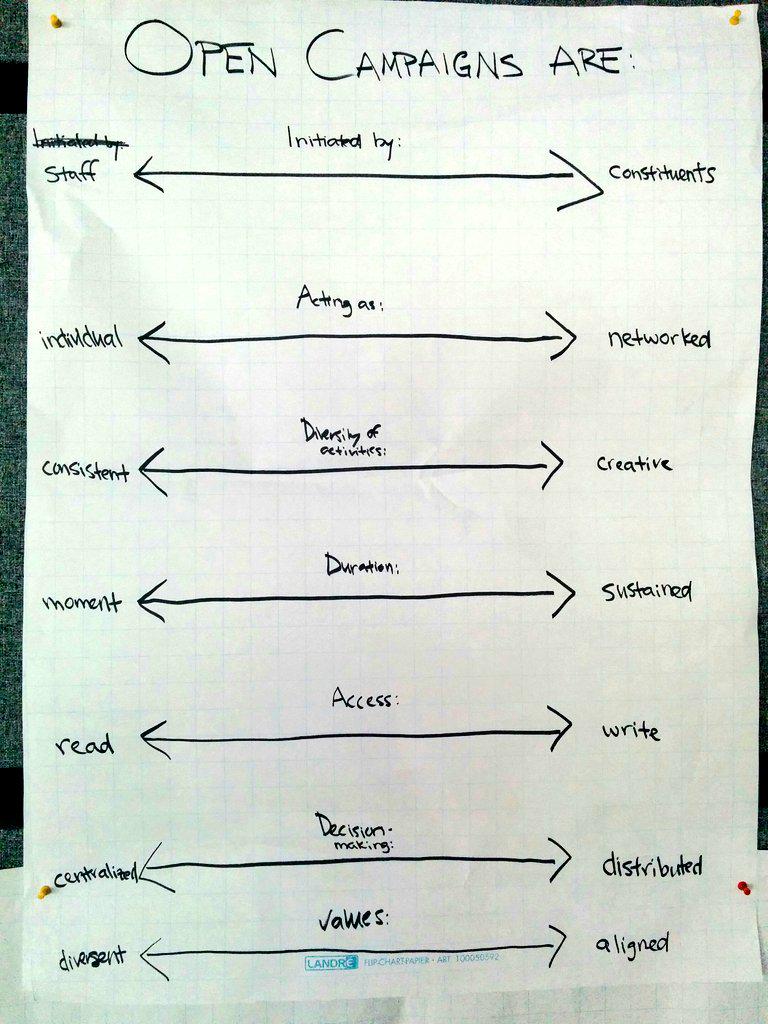

The Open Campaigns Camp in Berlin (#OCCBerlin) featured an intense three days of skill-sharing, brainstorming, and campaign jamming. Under discussion was everything from the meaning of “open” campaigns and big questions about when to engage volunteers in our work, to nitty gritty details about operationalizing openness and overcoming institutional barriers.

Here are four of my main observations from #OCCBerlin:

1) There are tiers of openness

The campers represented organizations in drastically different places. For some, engaging volunteers in any way was a new aspect of their work. Others had a degree of openness in their DNA, and are now pushing the envelope of grassroots-led campaigns. One of the greatest strengths of #OCCBerlin is that campers came from all sorts of affiliations and backgrounds — from the heads of major organizations to local volunteer coordinators, from international advocacy groups to freelance campaigners. This diversity fueled some of the best conversations and helped expose the very different ways different organizations approach these questions.

While there are many ways to classify organizations based on their openness (one session group tried) My gut is that there generally three tiers of open campaigns:

- Volunteer campaigns are campaigns that are guided and executed by staff, but with clear roles for anywhere between a handful and a couple hundred volunteers engaged in various parts of the work.

- Mass membership campaigns are campaigns that are guided and mostly executed by staff, with thousands to hundreds of thousands of individuals engaged in easy online tactics and hundreds of volunteers managed at scale to implement tactics such as local gatherings.

- Grassroots-led campaigns are campaigns that are mostly guided and executive by volunteers, with support from staff – including everything from a single petition on an open petition site to an unprompted campaign to get a local university to divest from fossil fuels.

2) There are three elements to the best open campaigns

Do open campaigns represent an improvement on traditional campaigns, or simply a variant? Campers were united in their belief in the power of open campaigns – as a simple matter of maths, you can do more when you have more people involved. Most campers also come from organizations that they would like to see become more open. Almost all social change groups could experiment with tactics from a higher one of the tiers mentioned above. That said, it became clear that the best open campaigns – the ones that were producing impact, where volunteers were engaging on their own and in large numbers, where organizations were getting more out than they were putting in — had three characteristics:

- A local action for people to take

- The chance of creating impact from that local action alone

- A strong theory for how many local actions result in collective impact

Consider campaigns to get municipal governments to express disapproval of a national government policy. There is a local action to take. There is a clear theory of how hundreds of cities and towns could send a powerful message that results in collective impact. But one town alone? The impact there is less clear. My level of enthusiasm will match my level of trust that all those other activists are going to get the job done in their towns, too.

Or consider the reverse, an effort to change laws all over a country, but one city at a time. Change one city’s laws, and you have a clear local impact. But the collective impact theory is weaker, because it takes a lot of difficult campaigns in a lot of cities to equal the weight of one national law. I may lack inspiration because the problem feels bigger than the solution.

In circumstances like these, it can be hard to produce truly open campaigns, because volunteers understandably lack either enthusiasm, the belief in victory, or a sense of creating big change.

Contrast these with something like 350.org’s divestment campaign, one of the clear open campaign success stories. There is a local action — getting a local institution to divest from fossil fuels. Victories can be easier to come by than in other efforts, and even one victory means fewer dollars for destructive oil and gas production. And collectively, all those wins are enough to pressure and hurt an entire industry. This is a case where volunteers can see how the local connects to the global, how they can actually create change, and how that change leads to change in the world. You can see how a campaign like this, once sparked, takes on its own energy.

3) There is a deep hunger for better metrics

Most people don’t become excited at the mention of new and different ways of measuring their work. Most people are not social change organizers at #OCCBerlin.

There is a deep hunger to move #BeyondVanityMetrics and explore better ways of measuring how engaged volunteers and supporters are and how well organizations are interacting with them. The earliest sessions on these topics drew excited crowds asking similar questions, and prompted more sessions as the camp continued. Lucky for me, the consensus was similar to the one expressed in my recent report, Beyond Vanity Metrics: People know that what they are measuring isn’t sufficient, but they are struggling to find new measurements and most importantly to change the way their teams think about metrics.

4) We have only begun to explore the next frontier

How do you spark an open campaign and keep momentum building? That is the role of storytelling. While it has always been important, storytelling takes on a new importance in open campaigns. As the tools and tactics of campaigning have been decentralized and put into the hands of supporters, the role of the organization is increasingly to curate stories and communicate a narrative — broadcasting a vision that allows volunteers to easily see their place in creating change, and sharing the case studies of other volunteers as models that can provide inspiration to others.

Social-change organizations have only begun exploring the new role of storytelling in open campaigns. And storytelling is by no means unique. As campers dove into the second and third days, it became obvious that there were huge thorny issues and challenges open campaigners had only begun to explore. For instance, what are the ethics of open campaigns — when are we putting volunteers at risk, or devolving risk from organization prepared to face it to individuals who are not? How do we operationalize openness in the everyday work of campaigning — crowdsourcing not just charismatic tactics but traditional staff activities such as design, research, or mundane but essential tasks? Tying together all of these threads, what does non-violent direct action look like in an open campaigns environment? We’re just beginning to explore these questions.

That sense that we are just beginning to tap into something extraordinarily powerful is what made the Open Campaigns Camp such a tremendous experience. Campers came from dozens of countries and all sorts of backgrounds. They were united by their belief in people-powered social change. They were smart and accomplished enough to share lessons learned, and humble enough to admit when they didn’t know the answer. The worldwide progressive movement is becoming more open, more volunteer-led, more oriented to grassroots supporters — and just beginning to realize our own potential.